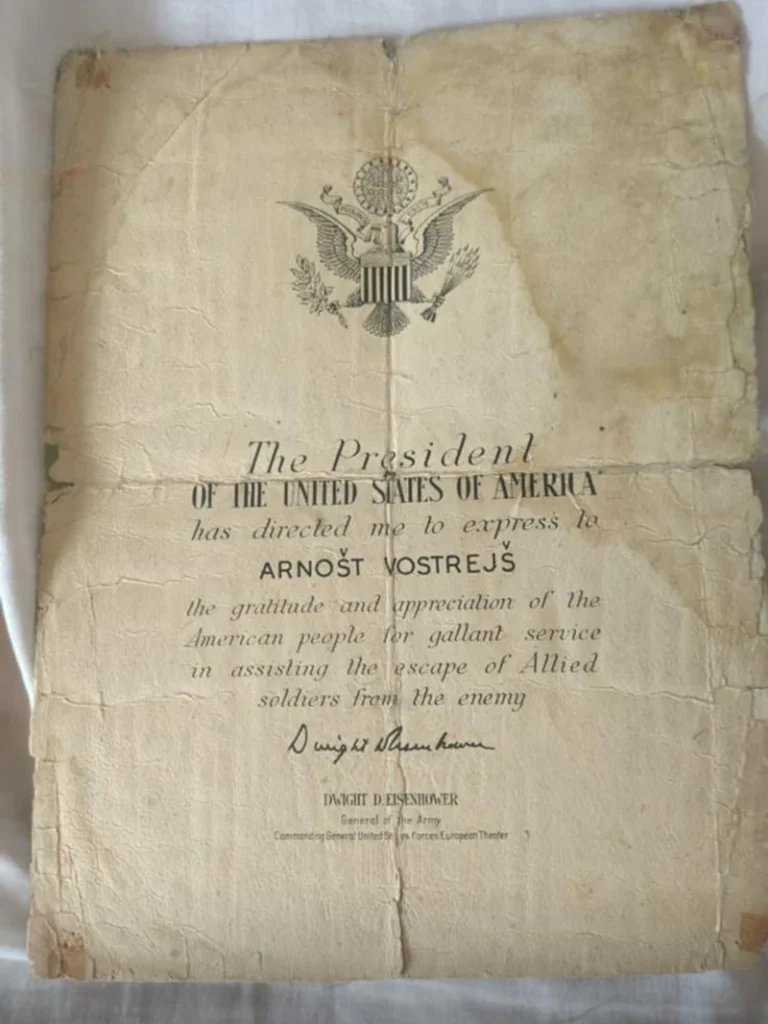

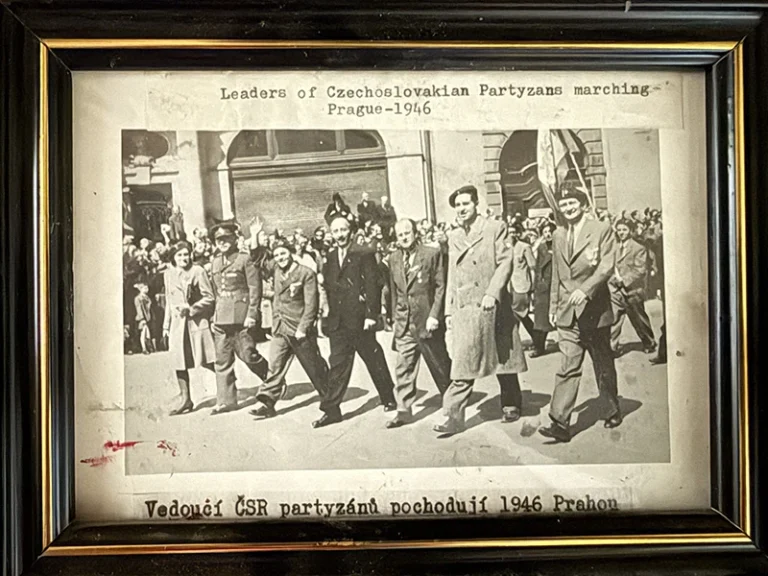

Here’s my dad. My father was head of the partisans during the Nazi occupation, when the Germans dominated our land. After the liberation, he marched with the victorious partisans and later became the second hand – the closest advisor – of President Edvard Beneš when he was elected president of Czechoslovakia. That was the moral and political stature of the man who gave me life.

I was born in April 1945, at the end of World War II, in a country house in Nihov, near Braunau. That house was not just our home: it was the headquarters of the partisans of the region. Under the mattress of my crib a machine machine was hiding. For my baptism, my father asked the German commander for a truce. The occupants withdrew, the guerrillas entered, baptized me into the chapel and celebrated until one of the girls asked for permission to go milking the cows. That’s how the party ended. It was some other time.

But peace lasted for little. After the liberation, Europe was distributed and, when the Russians entered Czechoslovakia, the presidents had to resign, were killed or thrown on the balconies. My father was called to interrogation with the chief general of the Czech Liberation Army, General Luza. They first asked the general whether he would support the new communist regime. He said no. He was killed right there. Then they asked my father. He said yes, knowing he wouldn’t live to tell. That same night, in February 1948, he crossed the border to Vienna, fleeing to save his life.

That’s where our odyssey started.

My mother, my sister – five years old – and I stayed in Bruno with my granny. I was three and a half years old. We crossed the border four times. The first was at night, in February, with snow covering everything. As they crossed no one’s land, the clouds opened and the full moon appeared. There were shots, dog barks, “hands up, or we killed them!” I said to my mom, “Mommy, raise your hands, please, they’ll kill you.” They took us to the border prison. My mother was interrogated under two lights; my sister and I went to a cell. The next day they let us go and we went back to my granny. My father managed to get my mother out of Vienna thanks to contacts he still kept.

The second time, a passerati – a smuggler of people – hired by my father came looking for us. On the way he took a bottle of slivovitsa, got drunk and left my sister and me all night in the snow. We were typing, but we were wearing brown-bear coats. At dawn he returned us to my granny’s house.

The third time, another passerati was successful. He took us to Bratislava by train. When my father saw us, he cried. A recite man, a guerrilla, head of Moravia’s partisans, crying when he remet his daughters.

We live in Vienna for a while, still under Russian occupation. Then we took a train to Innsbruck, where we spent a year in a migrant camp. They gave me sleeping pills so I wouldn’t talk in Czech if inspectors arrived; my sister knew how to shut up, I was too small. My father ran for Australia, Canada and the United States, but he didn’t want to go back to politics or intrigues. Finally, someone said, Chile. Nobody knew where it was. “South America – they said – where there are Indians with feathers.” And we’re off.

We arrived in Marseilles, we embarked on a war transport called Campana, we arrived in Buenos Aires and from there we flew on a military plane with canvas seats to Santiago. We were accommodated in the National Stadium’s shrimp. Then, some Czech Jews who had emigrated before helped us find accommodation in a garage in Providencia. My parents worked on everything they could. I studied at the Dunalastair, and my sister Alena, at the Deutsche Schule. Little by little, they put their fish together.

At the age of 13, I started skiing in Lagunillas. There I met a young man I fell in love with at first sight, and he met me. He was older; when he knew my age he almost died. We met again in Algarrobo, on the dock, and we fell back – like flies – for each other. That love accompanied us all our lives.

I joined the competition team, first in Lagunillas, then at the Catholic University Club in Farellones. I competed, I won, I was a national champion. In 1964 I traveled to Innsbruck for the Winter Olympics. My husband was in charge of the Chilean national ski team; I was part of the organizing team. There are photos of us in Maria Teresa and Strozzi, in Mount Hutt in New Zealand, and unbeatable memories of France, Spain and Andorra.

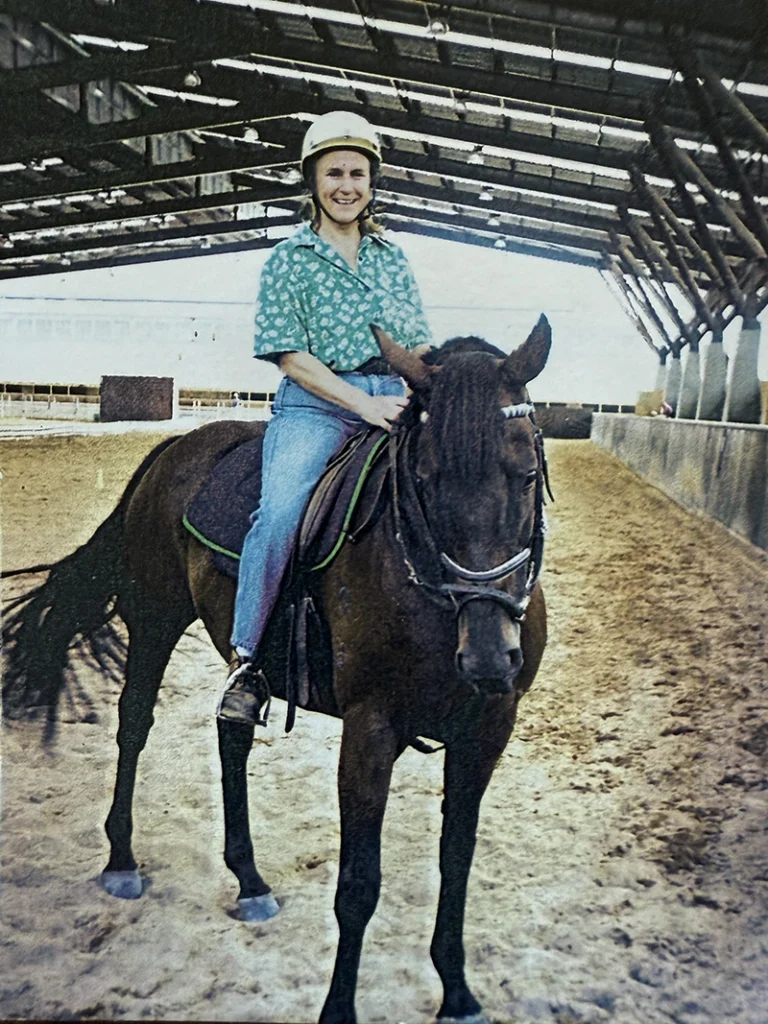

I studied music for three years at the Conservatory at the University of Sydney. I just wanted to sing in Russian. As I could not read it, I studied a Bachelor of Arts with a specialization in Russian at Macquarie University, from which I was later awarded to St. Petersburg and then to Lomonosov University in Moscow, the most prestigious of the Russian Federation. I played the harp at the Sydney Conservatory of Music. I rode Billy, the horse I won a lot of jumping show competitions with.

I lived the sea intensely: in Cook’s Bay, in Moorea, I saw a yacht called Gold enter the lagoon, capitulated by a French polynesian called Teki, with long curly hair, almost a local deity, the Maria Wahine. We sleep on board, we sail from island to island exchanging pineapples, bananas and fish. We spoke French, there were no tourists. It was a wonderful trip. In Sydney we sailed with friends at the Bird of Passage yacht, walking Pitt Water and the whole bay.

With my husband we represent Chilean and Spanish wines in Australia and the Philippines: Miguel Torres, Santa Rita, Santa Carolina, Concha and Toro, Undurraga. We organized wine tasts with Australian critics. At first they said, “The dyes pass, but the white ones are worse than some.” Then we brought Australian wines to Chile to show how they were made, how they were labeled. And they improved, they improved, they improved. We participated in the largest wine exhibition in the southern hemisphere. Our company was named after my husband, Celladane and Yunvale.

We also promoted South American skiing from Australia, when no one believed it could ski in Chile or Argentina. We created Condor Ski Tours, went through cities, made maps, opened roads. When we returned to Chile, we were received as kings in the ski centers.

Among family documents I keep an exceptional one: signed in fist and letter by Emperor Franz Joseph, giving my great-grandfather the title of nobility. Edward Noah. It’s stressed. I am a heir to that title and property in Hungary. The story was always there, with me.

Today, as I look at these photos – my father, the war, the flight, the ski, the sea, the music, the wine – I understand that my life was a succession of exiles and belongings, of crossed borders and built homes. It all started under a cradle that hid a machine gun. Everything continued with the certainty that, even in the midst of fear, you can always start again.

From Australia to the raising of Grand Pyrenees in Puerto Varas

When we felt that Australia had already given us everything it had to give us, we knew it was time to move on. We had lived that country intensely: worked, raised our four children and traveled much of that far-off world. The adventure was done. And then, Chile called us back.

Chile was never a foreign place. For years we were returning all winters, even when the children were still small. We came to ski at the end of the season, going through ski centers in Chile and Argentina, one after the other, as a ritual. Until one day, without drama, we understood that that stage had also come to an end. The big companies had taken control of the business, the pioneering spirit had been diluted, and there was no point in continuing to fight or stress over a market that had changed forever.

Then we decided to settle in Chile. At first, the plan was clear: Parelones. It was loaded with memories, friendships, shared stories. We dreamed of building a lodge there, a place that would pick up that whole past. We found a beautiful, corner place that belonged to Marisol Torrealba, former ski partner and team leader in Valle Nevado. We did everything that needed to be done… until reality appeared: the land was divided by half and part of it was listed as a reforestation area, under the administration of the Municipality of the Barnechea.

We went to the municipality, we investigated, we talked. They explained that in Farelones, during the first years of development, many sites were not properly delimited, which had led to conflicts of landslides to this day. The conclusion was simple and painful: we were not going to pay five thousand meters to receive only two thousand five hundred. So, with pity, we left that dream behind.

The next option was Chicureo. There we find a spectacular ground, on top, with a view to the Plomo, La Paloma and El Colorado. A corner place, five thousand meters, perfect. But before closing, we wanted to say hello to the neighbor. It was then that he told us, almost naturally, that he had just been attacked below, that there was a nearby population, that the sector had become insecure. A few days later, criminals went up the hill, assaulted us and stole. The children were deeply affected. The emotional cost was immense. That experience definitely closed that door.

We thought we’d go back to Las Condes, where we had a restaurant years ago. But it was no longer possible: everything was subdivided, densified. I even went with my niece Carlita to see the house we had built with Pelayo in Camino Fernández Concha, a beautiful work designed by Kato Casanueva, one of the best architects of the time. Seeing her was exciting… but it wasn’t ours anymore. The place had changed.

It was then that Pelayo, with absolute clarity, said, “Let us be serious. Let’s go south.” He gave me total freedom to choose, on one condition: to be near Puerto Varas. Thus began the search for a new nest.

We travel Frutillar, we stay at Clarita’s pension, we walk for months all the edge of the lake, looking, feeling, waiting. Until we finally find the place we are today. A completely peeled place, no trees, no garden, nothing. And there we started again: we designed the garden, built the house, shaped a dream from scratch.

Meanwhile, we rented a pallet cabin at the Hotel Puerto Pilar. But the hotel changed its owner: it moved from Benitez to Ernesto Pérez, who asked us for the place because he planned a complete remodeling. So we improvised. We had two containers that had arrived from Australia. We put them apart, we made them roof, floor, walls and a gate. Two trunks on the floor, one OSB iron on top, the mattress… and there we live while we were building.

It was at that stage that Bobby, a young, skinny, ill-cared sheep, appeared. We fed it every day. When we moved to the containers, Ernesto Pérez’s brother arrived with the dog: “Here’s the one who likes it so much.” I was happy… until Bobby killed the hens of neighbor Juanito and almost killed a cat they had given me. There were no fences, there were sheep and cows giving birth. It was impossible. We had to give it back. That day I said, “I can’t have dogs.”

Pelayo then remembered the Great Pyrenees.

And there begins another story.

Our children – two out of four – grew up in Australia. It was there that our daughter met Allan, when they were just children, meeting at the station on her way to school. From that children’s game was born a deep love. They married at the Saint James church in Sydney, the oldest in Sydney, with two ministers: one Anglican and one Presbyterian. A symbolic, beautiful, unlikely union.

Allan came from a traditional Presbyterian family and owned one of the largest stays in New South Wales: more than 100,000 hectares of sheep. There was born Eddie, my first grandson. In that stay we met the guard dogs, the Great Pyrenees.

That’s how we brought the first to Chile. Catarina, who still lives, was the first. Then came the crosses, the puppies… and one day he called us Douglas Tompkins. They needed these dogs to protect the cattle and avoid indiscriminate hunting of the puma, which was on the verge of extinction. We began to raise and distribute Grand Pyrenees throughout Chile and Argentina, from Calama to Punta Arenas.

And so, without realizing, we also contribute to saving the puma.

But that… that’s another part of the adventure. And it will continue.